SOr The Importance of Nutrition & Lifestyle Recommendations in Perimenopause, the Transition Period Before Menopause.

While many women go through menopause without medical intervention, some experience symptoms that can impact their daily lives and seek information rather than medication unless symptoms are severe. Offering clear, evidence-based, unbiased, and balanced information about the nature and duration of menopausal symptoms can empower women and help them make informed choices about their care (Hickey et al., 2024).

Facts:

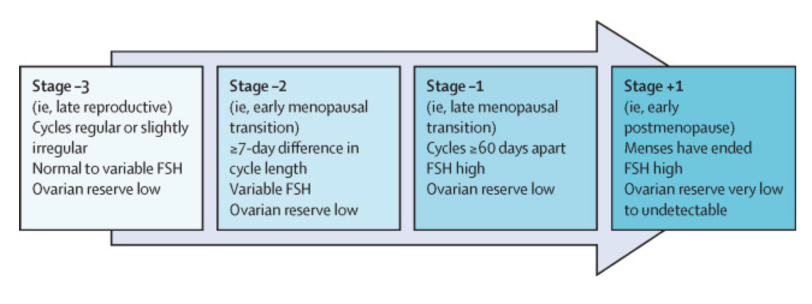

Stages of Menopausal Transition (Hickey et al., 2024, from Lancet):

**FSH (Follicle-Stimulating Hormone, is a hormone produced by the pituitary gland in the brain, which plays a crucial role in the reproductive system. It helps regulate the menstrual cycle and is essential for the growth and development of ovarian follicles, which contain eggs. FSH levels fluctuate during the cycle and peak around the middle, triggering ovulation, which is the release of a mature egg from the ovary).

**Low ovarian reserve refers to a reduced number and quality of eggs in the ovaries, often associated with a decrease in fertility. Women are born with a fixed number of eggs, which gradually diminish over time. Low ovarian reserve can occur due to several factors, including age, genetic factors, autoimmne diseases, medical treatment or lifestyle factors (smoking, high levels of stress).

Menopause occurs due to the age-related depletion of ovarian follicles, leading to a gradual decline in the endocrine functions that support female fertility. (Simpson et al., 2022). Menopause usually happens between ages 45 and 55, marking the point when menstruation has stopped completely for an entire year after the last menstrual period. In the transition phase called perimenopause, irregular menstrual cycles, including periods of amenorrhea (absence of menstruation), may occur for several years before menopause. However, hormonal shifts, which trigger physical and psychological changes, start even earlier in this process (Erdelyi, 2023).

Ovarian aging leads to fluctuations and, ultimately, the cessation of the production of Progesterone and Estrogen, the sex steroid hormones. These hormones are not only vital for female reproductive health, but their decline also impacts other areas of the body. They play crucial roles in the brain, skin, bones, muscle tissue, cardiovascular and genitourinary system, and metabolism, affecting the overall well-being of women (Gersh & Perella, 2021). Therefore, withdrawal of ovarian hormones in menopause may increase the risk of obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes (T2DM), cardiovascular diseases (CVD), tumors (especially hormone-sensitive breast cancer), cognitive decline & osteoporosis.

In addition, many women may experience common symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, headaches, acne, fibromyalgia, and increased joint & muscle pain. Emotional changes, including irritability and mood swings, may also occur, along with difficulties in concentration. The intensity and frequency of these symptoms can vary.

The European Menopause and Andropause Society (EMAS) highlights the significance of lifestyle recommendations in managing menopause, such as adopting a plant-based diet that aligns with national dietary guidelines or the Mediterranean diet, regular physical activity, addressing smoking and alcohol consumption, that can significantly influence menopausal symptoms, prevent excessive weight gain as well as age-related weight loss, and promote a healthy body composition (Rees et al., 2022).

So, what’s going on? Why? & What can we do about it??

During perimenopause and menopause, the reduction in Estrogen levels can:

I. Reduce the female body’s basal metabolic rate (BMR) by up to 250–300 kcal per day, boost appetite and affect fat distribution, leading to weight gain, typically increasing abdominal (visceral) fat (Erdelyi et al., 2023).

II. Decrease fat-free and skeletal muscle mass, which can result in sarcopenia (progressive loss of muscle mass, strength, and function, typically associated with aging that can be influenced by physical inactivity and poor nutrition, specifically inadequate protein intake). In some cases, this can lead to sarcopenic obesity, characterized by both excess fat and a reduction in muscle mass and function.

The prevalence of obesity increases with age, especially among middle-aged women, where 60–70% experience weight gain during menopause. Women in their midlife (ages 50–60) may gain approximately 6.8 kg per year.(Erdelyi et al, 2023).

In dietary treatment for obesity, creating a negative energy balance is crucial. Calculating actual energy requirements is essential based on an individual’s current body weight (Erdelyi et al., 2023), and should be tailored to an individual’s needs, considering gender, age, body mass index (BMI), and accompanied by moderate aerobic and resistance exercise (Yumuk, 2015).

To preserve or enhance fat-free body weight and skeletal muscle mass, protein consumption should represent aproximately 20% of total energy intake per day (Erdelyi et al., 2023).

III. Increase risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Dietary management of CVD should focus on maintaining a normal nutritional status, controlling high blood pressure (BP), and addressing unfavorable changes in blood lipid profiles (Erdelyi et al., 2023). Lifestyle (LS) modifications such as sodium restriction, alcohol moderation, healthy eating, regular exercise, weight control, and smoking cessation can all have health benefits beyond their impact on BP (Williams et al., 2018). Additionally, LS interventions are essential because they can delay the need for drug treatment or complement the Blood Pressure-lowering effect of existing drug treatment.

According to Gardner et al. (2023), strict adherence to a healthy diet can reduce the risk of cardiovascular mortality by 14–28%.

IV. Impact on fluid and electrolyte balance, often reducing thirst and decreasing fluid intake. Adequate fluid intake is crucial during perimenopause/ menopause for cellular metabolism, regulating temperature, detoxification, and maintaining gastrointestinal function. An individualized fluid intake of 33 mL/kg daily is recommended, ideally spread evenly throughout the day (Erdelyi et al., 2023).

V. Impact on Carbohydrate metabolism.

**Estradiol (a type of estrogen and a primary female sex hormone) has significant metabolic effects, supporting insulin’s effects on glucose metabolism. It can improve insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and suppress gluconeogenesis (the metabolic process by which glucose is synthesized from non-carbohydrate precursors in the liver, helping maintain balanced blood glucose levels (Alemany, 2021). Additionally, Estrogen has been shown to enhance the production of Adiponectin, a hormone secreted by adipose tissue (fat cells) that also plays a role in regulating insulin sensitivity, glucose metabolism, and fatty acid oxidation, all of which are essential for burning fat stores and promoting weight loss (Gersh & Perella, 2021).

During Menopause, Insulin secretion from the pancreas decreases. Furthermore, insulin sensitivity in muscles declines, leading to reduced glucose uptake and higher blood glucose levels, increasing the risk of insulin resistance and Type 2 Diabetes.

In the liver, worsening insulin sensitivity causes increased gluconeogenesis and lipogenesis (the process by which the body converts excess carbohydrates into fatty acids, which are then stored as fat in adipose tissue). These metabolic alterations can collectively contribute to the development of metabolic syndrome (Erdelyi et al., 2023).

(**Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of conditions that occur together, increasing the risk of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes. The main features of metabolic syndrome include elevated blood pressure, high blood sugar, excess body fat around the waist, and abnormal cholesterol or triglyceride levels).

Consuming carbohydrates with a low glycemic index and a high fiber content has a protective effect on health. When selecting carbohydrate sources, it is advisable to prioritize vegetables, whole grains, fruits, and dairy products without added sugars. Increasing fiber intake is particularly beneficial, as it can slow the absorption of carbohydrates, helping to maintain stable blood sugar levels (Erdelyi et al., 2023)

VI. Osteoporosis, a chronic condition that primarily affects women with low vitamin D levels, can lead to significant bone density loss.

Factors such as poor nutritional status, vitamin D deficiency, and certain medical conditions (overweight/ obesity/ sarcopenia, malnutrition, coeliac disease, IBD) can negatively impact bone health. LS changes, including maintaining a balanced diet rich in vitamin D and calcium, exercising regularly, and avoiding smoking and excessive alcohol consumption, are essential to reduce the risk of fractures (Erdelyi et al., 2023).

VII. Increased risk of hormone-sensitive breast cancer.

Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer among women in this stage, with key risk factors including overweight or obesity, regular alcohol consumption, and a sedentary lifestyle. Thus, adopting a balanced diet that includes regular consumption of cruciferous vegetables (such as cabbage, broccoli, and cauliflower) and at least 500 grams of vegetables and fruits daily is recommended (Erdelyi et al., 2023).

VIII. Dysbiosis and gastrointestinal complaints.

Estrogen impacts gut microbiota, while the microbiome can also affect serum estrogen levels. Probiotic supplementation in menopausal women has shown promising effects on cardiovascular risk factors by preserving the integrity of the intestinal barrier, which helps reduce bacterial translocation and systemic inflammation (Erdelyi et al., 2023).

IX. Sleep difficulties (may affect 40% to 56% of women in menopause), with many experiencing severe issues that lead to chronic fatigue with a negative impact on their quality of life. These disturbances can be attributed to hormonal changes, hot flashes, night sweats, and emotional factors like anxiety or depression.

Interestingly, insufficient sleep—less than 7–8 hours per night—correlates with higher risks of mortality and cardiovascular events, with those sleeping under 5 hours facing the most significant danger (Sejbuk, Mironczuk-Chodakowska & Witkowska, 2022).

**Furthermore, sleep deprivation can disrupt energy intake, glucose metabolism, and appetite regulation. Poor sleep is also linked to various chronic conditions, including obesity.

However, diet can play a critical role in melatonin production, which is vital for sleep quality. Foods high in tryptophan, such as fish, eggs, soy, nuts, and seeds, support melatonin production. And natural melatonin sources include cherries, strawberries fish and eggs.

Interestingly, either low protein intake (less than 16% of total energy) or high protein intake (19% or more of total energy) can be associated with difficulty falling asleep and poor sleep quality (Sejbuk, Mironczuk-Chodakowska & Witkowska, 2022).

IN SUMMARY or what’s really matters:

During perimenopause and menopause, adopting specific LS changes can significantly reduce the risk of diseases such as CVD, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), osteoporosis, and certain cancers.

Key recommendations include:

- Maintaining Healthy Body Weight: Aim for a BMI of 18.5–24.9 kg/m², with normal fat and skeletal muscle mass.

- Balanced Diet: Adhere to a balanced diet that meets energy, nutrient, and fluid requirements appropriate for age and activity levels.

- Regular Meal Timing: Establish a consistent eating schedule to support blood sugar regulation.

- Protein Intake: Aim for 0.8- 1.2 g of protein per kg of body weight per day (Erdelyi et al., 2023), with at least half of that coming from plant-based sources.**Consumption of soy and other phytoestrogens is widespread yet controversial. The research presents mixed findings on this topic. At the same time, soy isoflavones may alleviate the strength and frequency of menopausal symptoms; however, phytoestrogens could potentially interfere with the treatment of hormone-sensitive breast tumors (Erdelyi et al., 2023).

NEW Insights:

Interestingly, Prof. Stephen Simpson and his colleagues (2022) from the University of Sydney published a paper that the weight gain in the menopause transition may occur due to hormonally induced tissue protein breakdown, particularly in muscles and bones, combined with decreased energy expenditure. Additionally, the estrogen withdrawal likely contributes to a shift in fat distribution, particularly to the abdominal region, which is more metabolically active. Based on their research, hormonal changes trigger weight gain through a mechanism known as the Protein Leverage Effect, where progressive protein losses in the body lead to an increased appetite for protein. If dietary protein intake does not meet this demand, non-protein energy intake from carbohydrates and fats increases, contributing to weight gain (Simpson et al., 2022). Thus, modest changes in macronutrient ratio intake, total daily energy consumption, and physical activity during perimenopause can help prevent or mitigate these effects, making a significant difference in long-term health.

5. The daily recommended intake of carbohydrates should be at least 120 g, focusing on those with a low Glycemic load and high in dietary fiber, vitamins, and minerals (Erdelyi et al., 2023).

The American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics states that for adults with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes, dietary counseling by a registered dietitian nutritionist may improve the effectiveness of medical treatments and support longer life expectancy as well as prevent the progression of type 2 diabetes (Early & Stanley, 2018).

6. Fruits and Vegetables: Aim for 5 portions (400 g/day), focusing on 3–4 portions of vegetables and 1–2 portions of fruit (Herforth et al., 2019). Preferably fresh, seasonal, and locally grown.

7. A dietary fiber intake: The European Food-Based Dietary Guidelines (Herforth et al., 2019) recommend a minimum intake of 30 grams per day, while they also advocate for limiting added sugar intake, although the specific amount may vary depending on the country. However, the European Society of Cardiology recommends an even higher fiber intake of 35-45g for CVD prevention (Visseren et al., 2021).

**Increasing fiber intake can have several health benefits. By slowing down carbohydrate absorption, fiber helps stabilize blood sugar levels, which is vital for managing energy and reducing cravings. Its satiating properties can aid in weight management by keeping you feeling full longer, which can also prevent overeating.

8. Key Micronutrients: Ensure adequate intake of calcium, vitamin D, vitamin C, & B vitamins, preferably from natural sources.

**Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin vital in maintaining bone health and supporting immune function. It can be found in sources such as egg yolks, dairy products, offal, mushrooms and foods fortified with vitamin D. Around 80% of dietary vitamin D is absorbed in the small intestine. When UV-B radiation from the sun is insufficient, such as during the winter months or in regions with limited sunlight, dietary supplementation becomes necessary. Vitamin D supplements are most effective when taken with meals to enhance absorption.

**Clinical studies have shown that osteoporosis treatments achieve optimal results only when accompanied by sufficient vitamin D intake, typically greater than 1000 IU per day (Erdelyi et al., 2023).

9. Legume Consumption: Eat legumes (lentils, chickpeas, and beans) at least once a week.

10. Red Meat: Limit red meat and processed meats to occasional consumption.

11. Healthy Fats: Use cold-pressed vegetable oils and limit saturated and trans fats, aiming for less than 10% of total energy from saturated fat.

Adequate intake of monounsaturated (olive oil, avocado, nuts), polyunsaturated fatty acids (walnuts, flaxseeds, chia seeds, sunflower oil), and essential omega-3 fatty acids (fatty fish, flax & chia seeds, walnuts, pumpkin & hemp seeds) is necessary.

12. Salt Intake: Reduce salt consumption to as close to 5 g/day as possible (Williams et al., 2018), using herbs and spices for seasoning instead.

13. Fish Consumption: Eating at least two servings of fatty fish (e.g., salmon, mackerel) weekly can reduce the risk of CVD (Gardner et al., 2023).

14. Nuts and Seeds: Include 30 g of raw & unsalted nuts or seeds daily, adjusting for body weight.

15. Limit Sugary and Alcoholic Beverages.

16. Engage in regular exercise, practice mindfulness, & maintain a smoke-free lifestyle.

References:

Alemany, M., 2021. Estrogens and the regulation of glucose metabolism. World Journal of Diabetes, [online] Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8554369/ [Accessed 15 October 2021].

Early, K., B., & Stanley, K., 2018. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: The role of medical nutrition therapy and registered dietitian nutritionists in the prevention and treatment of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes, Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, [online]Available at: https://www.jandonline.org/article/S2212-2672(17)31849-X/fulltext.

[Accessed February 2018].

Erdélyi, A., Pálfi, E., Tűű, L., Nas, K., Szűcs, Z., Török, M., Jakab, A., and Várbíró, S., 2023. The importance of nutrition in menopause and perimenopause—a review, Nutrients, [online] Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10780928/ [Accessed 21 December 2023].

Gardner, C., D., Vadiveloo, M., K., Petersen, K., S., Anderson, C., A., M., Springfield, S., Van Horn, L., Khera, A., Lamendola, C., Mayo, S., M., Joseph, J., J. and American Heart Association Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health, 2023. Popular dietary patterns: alignment with American Heart Association 2021 dietary guidance: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, [online] Available at: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001146?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed. [Accessed 27 April 2023].

Gersh, F. and Perilla, A., 2021. Menopause: 50 Things You Need to Know. USA: Rockridge press.

Herforth, A., Arimond, M., Álvarez-Sánchez, C., Coates, J., Christianson, K., and Muehlhoff, E., 2019. A global review of food-based dietary guidelines. Advances in Nutrition, [online] Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6628851/. [Accessed 30 April 2019].

Hickey, M., LaCroix, A., Z., Doust, J., Mishra, G., D., Sivakami, M., Garlick, D. & Hunter, M., S., 2024. An empowerment model for managing menopause. The Lancet, [online] Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(23)02799-X/fulltext?dgcid=tlcom_carousel2_lancetmenopause24 . [Accessed: 7 November 2024].

Sejbuk, M., Mirończuk-Chodakowska, I., & Witkowska, A., M., 2021. Sleep Quality: A Narrative Review on Nutrition, Stimulants, and Physical Activity as Important Factors. Nutrients, [online]. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9103473/. [Accessed 2 May 2022].

Simpson, S., J., Raubenheimer, D., Black, K., I. and Conigrave, A., D., 2022. Weight gain during the menopause transition: Evidence for a mechanism dependent on protein leverage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, [online] Available at: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.17290 [Accessed 8 September 2022].

Visseren, F., L., J., Mach, F., Smulders, Y., M., Carballo, D., Koskinas, K., C., Bäck, M., Benetos, A., Biffi, A., Boavida, J.-M., Capodanno, D., Cosyns, B., Crawford, C., Davos, C., H., Desormais, I., Di Angelantonio, E., Franco, O., H., Halvorsen, S., Hobbs, F., D., R., Hollander, M., Jankowska, E., A., Michal, M., Sacco, S., Sattar, N., Tokgozoglu, L., Tonstad, S., Tsioufis, K., P., van Dis, I., van Gelder, I., C., Wanner, C., Williams, B. and ESC Scientific Document Group, 2021. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: developed by the Task Force for cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice with representatives of the European Society of Cardiology and 12 medical societies with the special contribution of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). European Heart Journal, 42(34), pp. 3227–3337, [online] Available at: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/42/34/3227/6358713?login=false. [Accessed September 2021].

Williams, B., Mancia, G., Spiering, W., Agabiti Rosei, E., Azizi, M., Burnier, M., Clement, D., L., Coca, A., de Simone, G., Dominiczak, A., Kahan, T., Mahfoud, F., Redon, J., Ruilope, L., Zanchetti, A., Kerins, M., Kjeldsen, S., E., Kreutz, R., Laurent, S., Lip, G., Y., H., McManus, R., Narkiewicz, K., Ruschitzka, F., Schmieder, R., E., Shlyakhto, E., Tsioufis, C., Aboyans, V., Desormais, I., ESC Scientific Document Group, 2018. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH). European Heart Journal, [online] Available at: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/39/33/3021/5079119#186437756. [Accessed 25 August 2018].

Yumuk, V., Tsigos, C., Fried, M., Schindler, K., Busetto, L., Micic, D. and Toplak, H., 2015. Obesity Management Task Force of the European Association for the Study of Obesity, European guidelines for obesity management in adults. Obesity Facts, [online] Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5644856/. [Accessed 5 December 2015].